Lutherans at Lugnuts

Lutherans #LoveLansing at the Lugnuts

Over 545 Lutherans from 11 LCMS congregations in the Greater Lansing area descended on Jackson Field in downtown Lansing on August 3, 2024. They gathered an hour before the game on the Tailgate Terrace for a stadium buffet and fellowship. There was as much food given as received, however, as the Lutherans brought food donations to the stadium to donate to the Greater Lansing Food Bank. The combination of fellowship, generosity, and being a presence in the community was the vision for the “circuit convocation” – a gathering of the circuit churches every three years. Tickets to the event, which included the all-you-can-eat buffet, were subsidized by the LCMS Michigan District and Church Extension Fund.

Over 545 Lutherans from 11 LCMS congregations in the Greater Lansing area descended on Jackson Field in downtown Lansing on August 3, 2024. They gathered an hour before the game on the Tailgate Terrace for a stadium buffet and fellowship. There was as much food given as received, however, as the Lutherans brought food donations to the stadium to donate to the Greater Lansing Food Bank. The combination of fellowship, generosity, and being a presence in the community was the vision for the “circuit convocation” – a gathering of the circuit churches every three years. Tickets to the event, which included the all-you-can-eat buffet, were subsidized by the LCMS Michigan District and Church Extension Fund.

“It was great to see so many of us from the area Lutheran congregations enjoying a beautiful evening at the ballpark together. The venue allowed us to be together but also right in the midst of our community at the same time. These are the people we are trying to reach with the Gospel,” said Pastor Bill Wangelin of Our Savior Lansing.

“It was great to see so many of us from the area Lutheran congregations enjoying a beautiful evening at the ballpark together. The venue allowed us to be together but also right in the midst of our community at the same time. These are the people we are trying to reach with the Gospel,” said Pastor Bill Wangelin of Our Savior Lansing.

Pastor Jim Pearl of St. John, St. John’s, commended, “God blessed us with a wonderful evening filled with fellowship, fun, and the opportunity to bless the community through donations to the Greater Lansing Food Bank.”

There were other groups noticeably present at the game, such as political campaigns and the Knights of Columbus. A group of nuns in their habits ate next to the “Welcome to Lutheran Night” sign. The people in the stands reflected the diversity of the area. It placed our LCMS churches in the context of the community to which we are sent. While the Lugnuts couldn’t pull off a win, the beautiful evening ended with a great fireworks display, lighting up the city skyline and the state capitol.

There were other groups noticeably present at the game, such as political campaigns and the Knights of Columbus. A group of nuns in their habits ate next to the “Welcome to Lutheran Night” sign. The people in the stands reflected the diversity of the area. It placed our LCMS churches in the context of the community to which we are sent. While the Lugnuts couldn’t pull off a win, the beautiful evening ended with a great fireworks display, lighting up the city skyline and the state capitol.

A few of the congregations annually go to the Lugnuts as a church event. Now that the circuit churches were drawn into this experience together, the pastors and lay leaders are talking about how to coordinate this event next year. We may not have the grant from CEF and the Michigan District or the Tailgate Terrace, but we could still bring the Food Bank donations and enjoy an evening together next year surrounded by the community we are called to serve.

A few of the congregations annually go to the Lugnuts as a church event. Now that the circuit churches were drawn into this experience together, the pastors and lay leaders are talking about how to coordinate this event next year. We may not have the grant from CEF and the Michigan District or the Tailgate Terrace, but we could still bring the Food Bank donations and enjoy an evening together next year surrounded by the community we are called to serve.

Onyx is in the Bible!

By Pastor Wangelin <><

Onyx is the name of our ministry dog at Our Savior Lutheran. God created certain animals to have a special effect on human beings, and dogs can bring comfort, joy, calm, and companionship to children and adults alike. When they see Onyx, children and adults smile, laugh, are comforted, and become more gentle and compassionate. These animals can bring out the best in us. We are so blessed to have Onyx as a part of the ministry team and student support services at OSL.

Onyx is a Gemstone

Onyx is in the Old Testament

Onyx is in the Old Testament

You won’t find Onyx the ministry dog in the Bible, but you will find onyx the gemstone. While mentioned in several passages of Scripture, a significant place is in the book of Exodus and the building of the Tabernacle at the base of Mt. Sinai. Onyx was featured in the garments of the high priest. In Exodus 28:9 we read, “You shall take two onyx stones and engrave on them the names of the sons of Israel.” These two onyx stones were set in gold filigree and acted like shoulder pads on the special vest of the high priest. Onyx appeared again in the ephod, or the gold chest plate that the high priest wore with twelve precious stones set in the front. The twelve stones represented the twelve tribes of Israel. Onyx was one of the stones mounted into the ephod. These priestly vestments and the use of onyx remind us how beautiful God is and how special it is to worship Him.

Onyx in the New Testament

Onyx in the New Testament

At the end of the book of Revelation, we read of the new heavens and the new earth. When Jesus comes again, He will make all things new. There will be no more death, or mourning, or crying, or pain, for the old order of things will have passed away. In Revelation chapter 21, we read about the heavenly Jerusalem coming down from heaven, the home of righteousness. This heavenly city is described as having streets of gold, gates made of pearl, and foundations decorated with twelve kinds of precious stones. The twelve foundations had on them the names of the twelve apostles of the Lamb. The previous stones on the foundation included jasper, sapphire, emerald, etc. One of them is onyx (in some translations it is sardonyx, a type of red onyx). The precious stones of the heavenly Jerusalem signify how beautiful and wonderful heaven will be in the loving presence of our Savior.

A Work in Progress

Raw onyx looks like a plain, simple rock. It looks like nothing special. It is rough and unattractive. But the

qualities are in there. An artisan knows how to bring out the best of this stone through a process of cutting, tumbling, polishing, and even etching and engraving. The result is beautiful and stunning. It shines and sparkles with reflective light. It is revealed as the valuable treasure it is.

We may feel sometimes like we are the raw onyx, nothing special, plain, rough around the edges, and worthless. But we are a treasure to God! God knows what we can be. He sees the potential and treasures us already in Christ. As a divine craftsman, God works on us in the process of sanctification, chipping away the rough edges, polishing, placing us in a setting, and creating something beautiful to reflect His light and glory. It may be a painful process at times. But God is careful and able to work good in all things, with the end result in mind.

We may feel sometimes like we are the raw onyx, nothing special, plain, rough around the edges, and worthless. But we are a treasure to God! God knows what we can be. He sees the potential and treasures us already in Christ. As a divine craftsman, God works on us in the process of sanctification, chipping away the rough edges, polishing, placing us in a setting, and creating something beautiful to reflect His light and glory. It may be a painful process at times. But God is careful and able to work good in all things, with the end result in mind.

In 1 John 3:2 it says, “Beloved we are God’s children now, and what we will be has not yet appeared; but we know that when He appears we shall be like Him, because we shall see Him as He is.”

God treasures us now as beloved children, but He is still working in our hearts and lives. We are a work in progress. Only when Jesus comes again, in the heavenly Jerusalem, will we see the finished product of what God is making us to be. We will shine like stars in the sky, like precious gems. We will be like Jesus, and reflect the radiant glory of God.

The name onyx reminds us of how beautiful it is to worship God, and that heaven is our home. We are a work in progress, as the Lord does His good work in our lives to bring out the best in us to His glory.

Blue Christmas

by Pastor Chris Deneen

I’ll Have a Blue Christmas, this year and each year.

This year, here at Our Savior, we are having a special service during Advent, a Blue Christmas service.

For many people, the holiday seasons are bright, they are filled with joy, they are holly and jolly, filled with gatherings, laughter, and moments that will make memories for a lifetime.

For many others, the holiday season isn’t always bright. It isn’t filled with joy, but with struggle. It isn’t filled with laughter, but tears. It isn’t filled with moments that will make memories for a lifetime, but it is a season that is left with just the memories of years that were holly and jolly. For many, this holiday season, is going to be blue.

That is where our Blue Christmas service comes in. This service is meant for those who are struggling this Christmas season. For some, it may be that they lost a loved one this year, in recent years, or at anytime and the grief weighs heavier during the holiday season. For others, it may be that they lost a job and aren’t sure what the next few days, weeks, or months may look like. For others, it may be that their holiday season has been turned completely upside down for whatever reason. For others, it may be a season where they feel alone. There are many reasons why someone might be having a blue Christmas.

I had never personally heard about a Blue Christmas service, until last year, the holiday season of 2022. About a week before Thanksgiving, I got a phone call from my Aunt. I had actually woken up to about 40 missed calls from my dad and my aunt. And then about 3:40 or so in the morning, I answered the phone. My mother had gone to be with Jesus. My mom had health concerns in the past, a major stroke in 2018, but for the most part she was doing well. It was an absolute shock. I, writing this today, can tell you that news changed everything for me. That day I got the phone call, I was originally scheduled to take my oldest daughter, Ida, to a Christmas play in Midland, MI with her “grammy,” my mom. That changed that day. It was the week before Thanksgiving, where I was scheduled to preach on Thanksgiving Eve, and at chapel at our school. That changed that day. We were still figuring out Thanksgiving plans. That all changed when we went from preparing a meal on Thanksgiving, to a funeral the day before Thanksgiving. Then I had to think about how, after Thanksgiving, the world would shift to the bright lights, the twinkling stars, the joyous season of Advent, as we prepare for Christmas. But for me, in the winter of 2022, I had something change: my mom, now celebrating the great celebration with Jesus, would no longer be at our Christmas, and for me, my Christmas was looking and feeling blue.

I will always carry the memories that I have of Christmases past with my mom. But there is no longer the opportunity to make new memories. At a meeting of area Lutheran churches, I found out that a sister congregation, Martin Luther Chapel on MSU’s campus, was having a Blue Christmas service.

I had no idea what it would look like. I had no real idea what to expect, but I went. And brothers and sisters, as sure as you are reading this blog post,

I am so glad I went.

In the long, dreary, dark days of the winter in Michigan, when days are dark longer than they are bright, where we often can go days or weeks without seeing the sun, where the darkest day of the year resides just days before Christmas, I am so glad I went.

Because what I experienced was this:

A raw, emotional, worship service, centered on the hope and joy of Jesus. Was it a dark day when I went? Absolutely, both metaphorically and literally. Was I having a blue Christmas? Absolutely.

But.

I was able to receive the word of God. I was able to know that I was not alone in my grief. I was able to, in the midst of a dark, dreary, blue Christmas, see the hope and light of Jesus that shines brighter than even the darkest of nights. I was able to hear and be reminded of this truth: My mom is with Jesus. That doesn’t turn the blue Christmas to bright and cheery, but it brings that glimmer of hope in the midst of the darkness.

That doesn’t mean that I won’t still grieve during the holiday season. That doesn’t mean I won’t get choked up almost every time I hear “Silent Night.” But it makes those dark, dreary nights and days and months seem a little less dark as the focus gets pointed back to the Light of the world. The Light who shatters the darkness, who shines within our lives, and who shines through others. No matter how blue or dark your Christmas may be, there is a light, there is THE light, who shines amidst the darkness. I pray that you can experience the light in the darkness at our Blue Christmas service on December 20th at 7 pm.

To answer a few questions that you may have:

Q: Who is invited to the Blue Christmas service? Is it only for people who have lost a loved one?

A: All are invited to join us. We are having this service especially for those people who are struggling with any kind of grief this Christmas season. We invite those who are struggling with addiction, depression or anxiety to join us. We invite those who mourn the loss of loved ones. We invite those who are lonely. We invite those who are battling illness or disease. We invite those who feel completely overwhelmed this holiday season. We invite those who are affected by war, whether they lost loved ones or know those who are near war-torn areas.

Q: Is this only for members of Our Savior?

A: No. If you are reading this, you are invited. And you are invited to invite someone you know that would be blessed by this service. This is a service meant to bring the hope and joy of Jesus to anyone who is struggling with any kind of hardships this Christmas season.

Q: What should I expect?

A: We will have a worship service, that gives adequate time to meditate and focus on the word of God. We will also have a time during the service where you may light a candle to bring your prayer before God. After the service, our Stephen ministers, trained, confidential, Christian listeners, will be willing to listen and pray with you. There will also be a time following the service for our service of healing, a time to be anointed with oil and prayed over. We will also have some light refreshments after the service, for a time of community.

Q: Is there a way for ongoing care from Stephen Ministers?

A: Absolutely. Our Stephen ministers are ready and willing to be that listening ear as you go through a hard time or season of life, through struggles, whatever that may be. They have extensive training and are ready to care for you. We pray that our Stephen ministers would be an extension of the love of Christ. If you are interested in meeting with a Stephen minister, and being paired up with one, you can contact our Church office, and our administrative assistant, Sue Sundstrom, will work with you on that confidential pairing.

Mission Middelburg 2023

worshippers and leadership continued on without missing a beat! We were blessed as the liturgy and even transitions between parts of the service were all done in song. The youth, about 14 of them, came up to dance and sing a couple songs. The elderly women’s choir sang, too. Pastor Khumalo’s wife, Lindiwe, was among them and was the song leader. We enjoyed noting that most of those choir members followed words in print, but Lindiwe use her phone! The OSL Mission team joined in with familiar songs and we sang two songs we had prepared to share before the congregation. They enjoyed our praises and one of the church board members later told us, “Next time 5 songs, not just 2!!”

worshippers and leadership continued on without missing a beat! We were blessed as the liturgy and even transitions between parts of the service were all done in song. The youth, about 14 of them, came up to dance and sing a couple songs. The elderly women’s choir sang, too. Pastor Khumalo’s wife, Lindiwe, was among them and was the song leader. We enjoyed noting that most of those choir members followed words in print, but Lindiwe use her phone! The OSL Mission team joined in with familiar songs and we sang two songs we had prepared to share before the congregation. They enjoyed our praises and one of the church board members later told us, “Next time 5 songs, not just 2!!” The service was extra special because Bishop Tswaedi was reinstating music leadership to unify the congregation and give them direction. He also commissioned two church planters to grow the Kingdom of God in their area. Pastor Wangelin preached the sermon and included some Zulu sentences which brought them joy and encouraged fellowship between us. Another highlight was seeing the gifted stained glass window that OSL presented to Pastor Mandhlo Khumalo before he left the U.S. in the entrance to the church and the previously given yellow, “Learn, Live, Share Christ” banner displayed near the altar. The team had brought two new banners to present to the congregation, which we presented during the service to Lindiwe

The service was extra special because Bishop Tswaedi was reinstating music leadership to unify the congregation and give them direction. He also commissioned two church planters to grow the Kingdom of God in their area. Pastor Wangelin preached the sermon and included some Zulu sentences which brought them joy and encouraged fellowship between us. Another highlight was seeing the gifted stained glass window that OSL presented to Pastor Mandhlo Khumalo before he left the U.S. in the entrance to the church and the previously given yellow, “Learn, Live, Share Christ” banner displayed near the altar. The team had brought two new banners to present to the congregation, which we presented during the service to Lindiwe  Khumalo. One stated, “The Lord is My Shepherd” and the other, “Praise the Lord of All Nations!” They also had an awesome close to worship with praises being sung while the youth danced a Congo line out of the church!! During the worship service while we were singing together, I couldn’t help but picture how majestic, loud, and joyful Heaven will sound as all nations and every language will be in praise together for our victorious Jesus! What a bond we have with God’s family in the world, through His Word, His Grace, and song. Truly, to God be the Glory!

Khumalo. One stated, “The Lord is My Shepherd” and the other, “Praise the Lord of All Nations!” They also had an awesome close to worship with praises being sung while the youth danced a Congo line out of the church!! During the worship service while we were singing together, I couldn’t help but picture how majestic, loud, and joyful Heaven will sound as all nations and every language will be in praise together for our victorious Jesus! What a bond we have with God’s family in the world, through His Word, His Grace, and song. Truly, to God be the Glory!By: Ryan Couser

Dear Our Savior Family, This is Ryan Couser and I had the privilege to be a part of the 2023 South Africa Mission Team. One of the memories I would like to tell you about is the day we spent at Doornkop, helping Mama Grace with her feeding Scheme. Although we think of the word scheme as

Dear Our Savior Family, This is Ryan Couser and I had the privilege to be a part of the 2023 South Africa Mission Team. One of the memories I would like to tell you about is the day we spent at Doornkop, helping Mama Grace with her feeding Scheme. Although we think of the word scheme as

We spent a long couple hours in Doornkop because we were busy playing frisbee, 4 square, soccer, and playing with jump ropes. Once the food was ready we had the kids line up and get their food of rice with a type of stew on top. Even after their meal they wanted to play with us some more which was cool to see. I liked the way we ended the day because we sang a couple more songs and prayed a prayer of blessing over the families, Mama Grace and this food ministry. My final memory I will never forget was after our closing, Ben, Alexander, and I started giving high fives to the children, and they wanted so many high fives I probably did the same kid five times. This day’s visit was very moving and was a great demonstration of the work God is doing, building up the kingdom all the way in Doornkop, South Africa.

We spent a long couple hours in Doornkop because we were busy playing frisbee, 4 square, soccer, and playing with jump ropes. Once the food was ready we had the kids line up and get their food of rice with a type of stew on top. Even after their meal they wanted to play with us some more which was cool to see. I liked the way we ended the day because we sang a couple more songs and prayed a prayer of blessing over the families, Mama Grace and this food ministry. My final memory I will never forget was after our closing, Ben, Alexander, and I started giving high fives to the children, and they wanted so many high fives I probably did the same kid five times. This day’s visit was very moving and was a great demonstration of the work God is doing, building up the kingdom all the way in Doornkop, South Africa.What is Advent?

One of the main ways that we celebrate Advent, and a way that you can celebrate Advent at home during this season, is by lighting an Advent wreath, which you will see at the front of the church during Advent! An Advent wreath is a wreath, with 4 or 5 candles. The 4 candles have specific meanings. The first two candles, which are blue or purple, stand for hope and peace. Hope and peace are two of the main components of Advent. As we wait for the coming of Jesus, as we wait for Christmas, we wait with hope! We wait knowing that Jesus has come into this world, and through His life, he saved us from our sins. The hope that we have is that it isn’t on our doing, but what Christ did coming into this world, as a gift from God, as we read in Ephesians 2:8-9, “For it is by grace you have been saved, through faith—and this is not from yourselves, it is the gift of God—not by works, so that no one can boast.”

One of the main ways that we celebrate Advent, and a way that you can celebrate Advent at home during this season, is by lighting an Advent wreath, which you will see at the front of the church during Advent! An Advent wreath is a wreath, with 4 or 5 candles. The 4 candles have specific meanings. The first two candles, which are blue or purple, stand for hope and peace. Hope and peace are two of the main components of Advent. As we wait for the coming of Jesus, as we wait for Christmas, we wait with hope! We wait knowing that Jesus has come into this world, and through His life, he saved us from our sins. The hope that we have is that it isn’t on our doing, but what Christ did coming into this world, as a gift from God, as we read in Ephesians 2:8-9, “For it is by grace you have been saved, through faith—and this is not from yourselves, it is the gift of God—not by works, so that no one can boast.” Finally, the last candle, which is blue or purple, stands for love. None of this, Advent, Christmas, Jesus coming into the world, would be possible without God’s love for us. In John 3:16, we read, “For God so loved the world that he gave his one and only son, that whoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life.” That love is what brought Jesus to the earth. That love is what we celebrate during Advent.

Finally, the last candle, which is blue or purple, stands for love. None of this, Advent, Christmas, Jesus coming into the world, would be possible without God’s love for us. In John 3:16, we read, “For God so loved the world that he gave his one and only son, that whoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life.” That love is what brought Jesus to the earth. That love is what we celebrate during Advent.150 Years of Lutheran Education

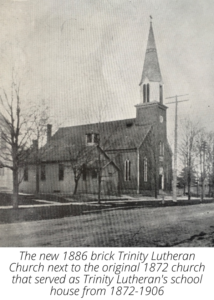

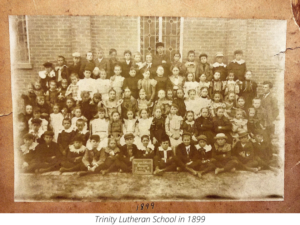

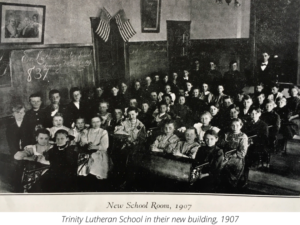

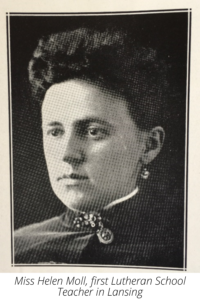

churches of that era. Classes were held in the church building built in 1872, and when the congregation built a new sanctuary in 1886, the old church continued to serve as the school building.

churches of that era. Classes were held in the church building built in 1872, and when the congregation built a new sanctuary in 1886, the old church continued to serve as the school building.

In the 1990’s, the church and school buildings were in need of greater repair and investment, while the families being served were scattered across the greater Lansing area. The original families who lived near the church were now older and their kids were grown. The school began to decline. After prayerful discernment, the church leadership proposed that the church consider moving to a new location that would better serve the greater Lansing area where the school ministry could thrive again. This

In the 1990’s, the church and school buildings were in need of greater repair and investment, while the families being served were scattered across the greater Lansing area. The original families who lived near the church were now older and their kids were grown. The school began to decline. After prayerful discernment, the church leadership proposed that the church consider moving to a new location that would better serve the greater Lansing area where the school ministry could thrive again. This  would be another bold move for the Kingdom that required sacrifice and commitment to the ministry. Land was donated to the church in Delta Township, and in 2008, construction began on a new church and school simultaneously. Once again, the church worshipped in the school gymnasium for a brief time until the sanctuary was completed. The building was dedicated on November 2, 2008, with Lutheran Hour Speaker Ken Klaus delivering the dedicatory sermon. The church was to be a house of prayer for all nations.

would be another bold move for the Kingdom that required sacrifice and commitment to the ministry. Land was donated to the church in Delta Township, and in 2008, construction began on a new church and school simultaneously. Once again, the church worshipped in the school gymnasium for a brief time until the sanctuary was completed. The building was dedicated on November 2, 2008, with Lutheran Hour Speaker Ken Klaus delivering the dedicatory sermon. The church was to be a house of prayer for all nations.Good Friday Prayer Guide

Tre Ora (The Three Hours)

God

Psalm 33:18 –“The eyes of the LORD are on those who fear Him, on those whose hope is in His everlasting love.”

Prayer Starter: Lord God, Heavenly Father, Your heart was broken when You had to send Your Son, Jesus, to the cross for the sins for which I, and all the world, deserved judgment. May my heart be broken as well, Father, for the things which break Your heart.”

Hebrews 12:2 –“Let us fix our eyes on Jesus, the author and perfecter of our faith.”

Psalm 62:1 –“My soul finds rest in God alone; my salvation comes from Him.”

2 Peter 1:2 –“Grace and peace be yours in abundance through the knowledge of God and of Jesus our Lord.”

Matthew 1:47 –“My spirit rejoices in God, my Savior.”

51, 22, 103, 86, 69, 63, 119:169-176

The Seven Last Words on the Cross

Luke 23:34 – “Father, forgive them, for they do not know what they are doing.”

Luke 24:43 – “Today you will be with Me in paradise.”

John 19:26-27 –“Dear woman, here is your son. Here is your mother.”

Matthew 27:46 –“My God, my God, why have you forsaken Me?.”

John 19:36 – “I am thirsty.”

Luke 23:46 – “Father, into Your hands I commit My spirit.”

John 19:30 – “It is finished.”

Easter Devotion

Easter Devotion

As we celebrate Easter, we are reminded that Jesus is no longer in the tomb! He is risen indeed! This is the greatest news ever. Christ was laid in the tomb on Friday, but death could not conquer our Lord who is victorious over sin, death, and Satan. That changes everything: our past, present, and future, and we are granted new life.

–Romans 6:6

We were once enslaved to sin, but through the death and resurrection of Jesus we are no longer held in that past. We no longer live as we used to, held down by our own sinful ways. Our sins were taken to the cross by Christ and He has forgiven us. The past is no longer what defines us. We are defined by the cross of Christ, which sets us free, and makes us heirs to the kingdom of God.

Future

“He has caused us to be born again to a living hope…to an inheritance that is imperishable, undefiled, and unfading, kept in heaven for you.”

–1 Peter 3:3-4

We have been given an inheritance that cannot be measured. On the cross, Christ won for us eternal life. Through that death and resurrection we are made heirs with Christ to the heavenly kingdom! While we are new creations here on earth, we can be certain that our eternal life has been won for us.

Prayer

Share prayer requests with each other and also pray for those who are not able to be with you.

Let us pray: Almighty God, we thank you for sending your Son, our Savior, Jesus into this world, in order that we might be saved from sin, death, and the devil. Give us hearts of hope and joy to share your light into this world. Remind us that we are no longer enslaved to sin, but we are freed by the sacrifice that Jesus made for us. Amen.

-Luke 24:6

Celebrating Baptism Birthdays

When we have something worth celebrating, we need to celebrate it! As the dreary days of January turn to February then turn to March, as winter drags on, there’s always a time for celebration. What a gift God has given us in our baptisms, something worth not just remembering daily, but celebrating daily. Here at Our Savior, we love baptisms. They are always an exciting addition to a Sunday service, as we get to welcome the newest member of God’s family and Our Savior! In baptism God adopts us as His children, and we receive this gift joyously, as God gives it freely.

In baptism, we receive several gifts, wrapped up into this one divine gift, given through ordinary water with the Word of God. We receive the forgiveness of sins (Acts 2:38), the Holy Spirit (Acts 2:38), and eternal life (Romans 6:4). What a great gift and joy baptism is and definitely worth celebrating! In baptism we are washed clean of our sins, and made righteous before God. (Titus 3:5-7) The Holy Spirit, the sanctifier, works saving faith within us, and helps us to grow and be strengthened in our faith. Finally, we receive eternal life. As we are baptized into Christ, into His death, the words from Paul ring true, “We were therefore buried with Him through baptism into death in order that, just as Christ was raised from the dead through the glory of the Father, we too may live a new life.” (Romans 6:4)

What a joy that is! What a wondrous gift we’ve been given by our Heavenly Father, as he adopts us into His family, and gives us that new birth, that regeneration. We hear Jesus talking about this new birth in His conversation with Nicodemus in John 3. Jesus tells Nicodemus that in order for one to be saved, they must be born again. Nicodemus is very unsure about what Jesus means. Jesus explains it this way in John 3:5-6, “Very truly I tell you, no one can enter the kingdom of God unless they are born of water and the Spirit. Flesh gives birth to flesh, but the Spirit gives birth to spirit.” When we are baptized, we are made new creations, and we are given new life, a life to live as holy, chosen people of God.

What a joy that is! What a wondrous gift we’ve been given by our Heavenly Father, as he adopts us into His family, and gives us that new birth, that regeneration. We hear Jesus talking about this new birth in His conversation with Nicodemus in John 3. Jesus tells Nicodemus that in order for one to be saved, they must be born again. Nicodemus is very unsure about what Jesus means. Jesus explains it this way in John 3:5-6, “Very truly I tell you, no one can enter the kingdom of God unless they are born of water and the Spirit. Flesh gives birth to flesh, but the Spirit gives birth to spirit.” When we are baptized, we are made new creations, and we are given new life, a life to live as holy, chosen people of God.

If you have been given a new birth, then you have to celebrate that. Going from enemies of God to part of His family and heirs to the eternal heavenly kingdom?? That is worth celebrating!

Here at OSL, that is exactly what we did.

Here at OSL, that is exactly what we did.

This past calendar year, 2021, in the midst of the COVID pandemic, we had 33 baptisms. 33! That is a huge number. A big year here is hitting double digits. 33, that is a great number, and all thanks be to God for that. Of that number, we had 6 adults, 14 infants, and 13 students. Normally we would expect to have a majority of infants, but this past calendar year we had more students and adults than infants. Thanks be to God for the ministry that we are able to do through our school and early childhood center.

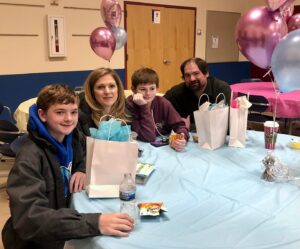

At the beginning of December, there was a meeting with some volunteers, and the planning for the Baptism Birthday party was underway. One of the major things we had to decide, was how do we celebrate this gift of God? As any good party goes, we knew we would need a few key items. Refreshments, cake of some kind, and a gift bag. We had a great spread of each of these. We had some wonderful refreshments, some cupcakes to keep things a little more individualized, and a gift bag for each of those who were baptized. And on January 9th, as we celebrated the baptism of Jesus in our services, during our coffee hour, we celebrated.

In the gift bags we had several items to celebrate and remind those baptized of their baptism. One of the main things, were two baptismal stickers. One was a sticker reminding, “I am Jesus little lamb.” This is a great reminder, that we are made children of God, sheep of our Great Shepherd. The other sticker that each baptized person received, was, “God’s own child I’ll gladly say it, I’ve been baptized into Christ.” This reminds of that great gift of being adopted into God’s family.

In the gift bags we had several items to celebrate and remind those baptized of their baptism. One of the main things, were two baptismal stickers. One was a sticker reminding, “I am Jesus little lamb.” This is a great reminder, that we are made children of God, sheep of our Great Shepherd. The other sticker that each baptized person received, was, “God’s own child I’ll gladly say it, I’ve been baptized into Christ.” This reminds of that great gift of being adopted into God’s family.

We also had a baptismal Chrismon in each gift bag as well. It was in the shape of a star with a cross in the middle. This “Christ monogram,” was another reminder of how through baptism, we are baptized into Christ, His death and resurrection.

Along with other small candies in the bag, we also had an age appropriate gift. All of our students and infants under the age of 8 received a stuffed lamb. This is a reminder that we are lambs of God, and at the same time, something for those children to be able to physically hold onto and cling to, reminding them of their faith in Christ.

The students that were between the ages of 11 and 14, received a wall cross that they could put up in their rooms, and have as a daily reminder of their baptism into the death of Christ. Finally, the adults received a devotional booklet. This is a way for them to continue to grow in their faith at a deeper level.

The students that were between the ages of 11 and 14, received a wall cross that they could put up in their rooms, and have as a daily reminder of their baptism into the death of Christ. Finally, the adults received a devotional booklet. This is a way for them to continue to grow in their faith at a deeper level.

Why was this a focus for us here at Our Savior? Because it is absolutely something worth celebrating. When we receive gifts, we celebrate. When we see God working in our lives, we celebrate. When something amazing happens to our family or friends, we celebrate! If you have all three of these things happening at once, we have to celebrate! We give thanks to our God and Father, who invites us to come to the font, who invites us to partake in this sacrament, who invites us into His family. We celebrate the gift of God because HE gives us this gift freely, that we may receive forgiveness of sins, redemption and regeneration, and ultimately eternal salvation with our God and our King. Does that seem worthy of celebrating? Absolutely.

Our Savior Food Bank in a Pandemic

What’s been happening at the Food Bank lately?

This is a question we hear from people who know that the Our Savior Food Bank provides food assistance through the Greater Lansing Food Bank to hundreds of families in the South Lansing area. Thankfully, by God’s grace, the Food Bank continues to serve people with food, household supplies, gently used clothing, and smiles and hugs that radiate God’s grace and goodness.

A young woman came to the food bank the other day with a baby and small child. She was on her own after fleeing a violent husband who was abusing her and the children. As she was being  helped by the Food Bank volunteers, she asked if they had any diapers. She stated that if Social Services found out her baby didn’t have any diapers, she feared they would take the children away from her, and she began to sob. Director Sharon Miller asked the woman if she was willing to come around the corner, which she was. Members at Our Savior had given Sharon some Kroger gift cards, and said, “Give these to the people you think are the most in need.” Sharon gave the $50 Kroger gift card to the young mother and said, “Here, go and use this to buy some diapers. We’ll makes sure you have enough groceries. In fact, you can come twice a week instead of once a month, and we’ll take care of you.” The mom began to sob again, this time tears of joy. The little child with her looked up at Sharon and said, “I’m hungry.” Sharon had to hold it together as she helped this family get the food they needed.

helped by the Food Bank volunteers, she asked if they had any diapers. She stated that if Social Services found out her baby didn’t have any diapers, she feared they would take the children away from her, and she began to sob. Director Sharon Miller asked the woman if she was willing to come around the corner, which she was. Members at Our Savior had given Sharon some Kroger gift cards, and said, “Give these to the people you think are the most in need.” Sharon gave the $50 Kroger gift card to the young mother and said, “Here, go and use this to buy some diapers. We’ll makes sure you have enough groceries. In fact, you can come twice a week instead of once a month, and we’ll take care of you.” The mom began to sob again, this time tears of joy. The little child with her looked up at Sharon and said, “I’m hungry.” Sharon had to hold it together as she helped this family get the food they needed.

The Our Savior Food Bank has been supporting the food-insecure population of south Lansing since the mid-1990’s. It is located in the former OSL parsonage, where our first pastor, Pastor Bickel, and his wife Dorothy raised seven children, on the property at our former location on Holmes Road, just west of MLK. When Our Savior Lutheran Church and School relocated to Delta Township in 2008, the Food Bank was an important connection to our old neighborhoods.

Food Bank Director Sharon Miller coordinates over a dozen volunteers who work to organize and sort donations and process food orders from the clients served by the Food Bank. These clients come to us through the Greater Lansing Food Bank, which provides deliveries of food at discount prices and serves as a clearing house for requests. While our Food Bank needs to follow the rules and policies of the Greater Lansing Food Bank, we are still able to bring our own unique blessings to this ministry. Government-issued food stamps can only be used for food – things consumed by mouth – and do not cover any hygiene products or cleaning supplies that we often pick up at the grocery store in addition to our food. Our Food Bank offers a number of “extra items” in addition to groceries, including health and cleaning products, gently used clothing, frozen meat, and school supplies.

Not only does the Food Bank serve general clients through the Greater Lansing Food Bank, but there are special segments of the population that we particularly are there for. Our Food Bank is known by the Department of Veterans Affairs as having a special interest in assisting veterans, and so we get a number of them who have fallen on hard times. The Department of Mental Health utilizes our food bank, and often the case workers themselves come to shop on behalf of their clients, who are too unstable or violent to come to the Food Bank in person. These case workers express their appreciation for our Food Bank, the volunteers, and how this is a blessing to the people they serve. Another special group is parolees, who are often turned down by other Food Banks. Our Food Bank has welcomed them and helped them get on their feet.

Prior to the pandemic, the Food Bank was one of the largest in Ingham County, serving nearly 100 families a week (30-35 families 3x a week), almost 10,000 people a year. The reputation of the Food Bank was that it went the extra mile to get people the help they needed, with a loving and caring group of volunteers who work there.

During the shut-down in 2020, the Food Bank was also closed for several months. This weighed heavy on the hearts of the volunteers who knew the families they served and their needs. A number of mobile food pantries popped up to serve the community, and additional government assistance helped fill in some of the gaps. A lot of decisions had to be made when the Food Bank reopened in August 2020. How should the procedures and facility be modified? Which volunteers were healthy and confident of returning? What health protocols should be in place? The volunteers were willing to make it all work. Gary Kandler built a Plexiglas window at the service counter and framed it in. New procedures and protocols had to be learned and adapted. With mobile food pantries also serving the area, the Food Bank clients dwindled, and when they reopened they were open only two days a week, by appointment only, with the volunteers who were able and willing to return.

In the past year, the process for coming to the Food Bank has been streamlined and improved, and while several area food banks closed due to lack of participation, things are starting to pick up at the Our Savior Food Bank again. They are still open twice a day, but now serving up to 19 families a day. Sharon Miller says that while the worst cases tended to be the elderly in the past, now they see people of all ages who are in desperate need. People who were hunkered down during the pandemic in miserable conditions are now starting to reach out for help. The Food Bank is there to assist them.

Several people from the community have dropped off donations to the Food Bank, often unannounced and unaffiliated with Our Savior. A random gentleman from the neighborhoods recently came to the door and gave the volunteers $55 and said, “Here, give this to someone who could really use it.” He trusted the Our Savior Food Bank to help the people who needed it the most.

We pray that our Food Bank can continue to be a blessing to the community, especially through the pandemic. We anticipate numbers slowly but steadily increasing, and at some point we may need to go back to being open three days a week. The possibility lies in the future of expanding the services provided there, such as ELS classes, life improvement skills, and spiritual care of some kind.

For those who have fallen on hard times, and are in need of grace, they find that and so much more through the smiles, encouragement, and extra items at the Our Savior Food Bank.